The Artists of Sand City

Ignacio kept his distance while I went to business, bargaining with the young man in charge of that family's merchandise, but as we went back and forth amicably in Portuguese, the rest of his family came out to watch. It was unnerving at first, and then fun, as their eyes scanned back and forth between us and as the two of us batted numbers back and forth.

One lazy weekend afternoon in Maputo, Ignacio mentioned the Sand City. "Have you seen it?" he asked me enigmatically. "Until you've been there you haven't seen Maputo." It was a challenge I couldn't resist, and we decided to beat the heat by driving up to the Sand City for a look around while the rest of Mozambique's quiet capital rested. Maputo's streets are paved and clean, but the pavement ends abruptly at the north end of town, and as Ignacio downshifted to maneuver his little car onto the dirt roads, we entered a new world.

At the edge of Maputo we rumbled past the hulking remains of an old 10 story hotel under construction in the late 1970s when the Portuguese were forced to abandon their colony. They did as much damage to it as they could before leaving Mozambique, a trend they repeated elsewhere throughout their former colony, filling toilets with concrete, ripping down wiring, carrying off everything of value from furniture to light fixtures. The Mozambicans decided their most evocative response would be to leave the building standing, incomplete, wasted. It stands as a monument to colonial avarice and rancor, and reminds Mozambicans to this day to treasure their independence. From that auspicious monument we entered the Sand City.

It's not fair to call the Sand City a slum, as the pejorative lacks any sense of the community pride that pervaded the community, but it's true the Sand City lacks all of the amenities that the capital just down the road makes prevalent, from running water to sanitation and trash collection. The locals are fishermen and shell fish harvesters, run bustling local markets, and fabricate things for sale elsewhere. Ignacio took me to where a local woman was selling mussels harvested from Maputo Bay and bargained with her for a pailful to take home to dinner that night. I bargained a photo out of the conversation.

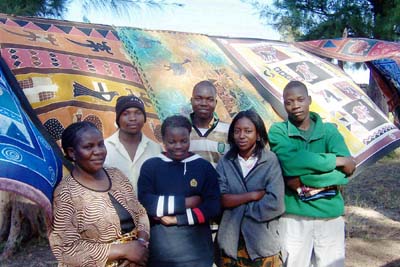

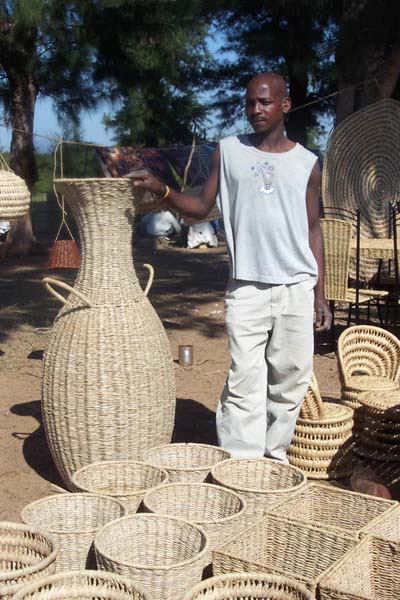

Local artisans line the sides of the main road, displaying pieces of astonishing intricacy and gorgeous workmanship. I marvelled over tables created from woven fiber stretched over steel frames, and carved wooden pieces too delicate to imagine having shaped by hand from a single piece of wood. But what really caught my eye were the gorgeous batik fabrics. I enjoy using the word batik, from the Indonesian language (Bahasa). I saw miles of delicately died and printed batik fabric when I lived in Indonesia, but African batiks are a world apart, even in their fabrication, and I couldn't resist taking two home. For one, the themes and colors are decidedly African and reflect different subject matter. I saw lots of bold patterns and rich shades of brown, giraffes and tigers and stripes of all metrics.

Ignacio kept his distance while I went to business, bargaining with the young man in charge of that family's merchandise, but as we went back and forth amicably in Portuguese, the rest of his family came out to watch. It was unnerving at first, and then fun, as their eyes scanned back and forth between us and as the two of us batted numbers back and forth. Indonesia was where I learned to bargain as well, though I gained experience in Central America. But bargaining in Latin America is decidedly different from bargaining in Africa, and the two of us bargained and presented counter-offers for ten minutes while the family watched. The trick is to remember it's a friendly transaction, almost a sport. It's also important to remember you start with every disadvantage in the world. "How much is the real price?" a friend once asked in Indonesia. There is no real price. It has to do with the family's need that day, their assessment of your ability to pay, and how much energy they have put into their work. I left the Sand City with two tapestries: a gorgeous, deep blue one with an aquatic motif, and a rich brown one inset with a happy-looking giraffe.

But I left as well with good memories of the Sand City. Far from being any sort of desperate, Third World hellhole, the Sand City was just that, a city with a personality and pride of its own, whose only crime was poverty and a lack of the services we would call fundamental rights just about anywhere else. But faced with hard conditions, the locals have taken it upon themselves to improve their lifestyle the only way they know how: by producing with their hands. This is the lesson of ground-up development: that it is most important to provide the poor with a level playing field and training and skills to take charge of their own destiny. Given the freedom to improve their lifestyles, they will.

Trackbacks

The author does not allow comments to this entry

Comments

Display comments as Linear | Threaded